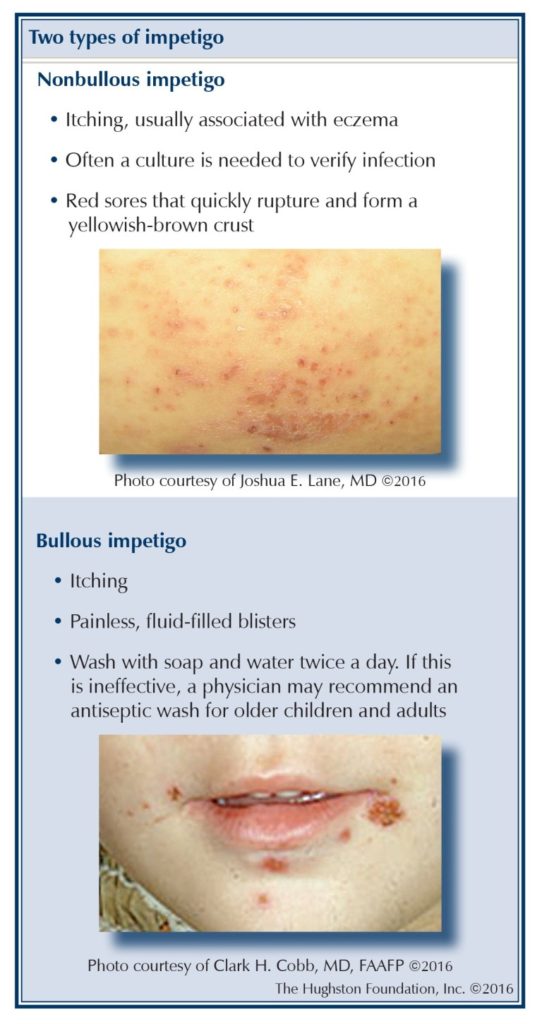

If you are an athlete, you have a greater risk than most people of contracting impetigo, a highly contagious skin infection that affects about 2% of the global population annually. The term impetigo comes from the Latin verb impetere, meaning to attack. It refers to the breakouts or skin eruptions that characterize the disease. Impetigo has 2 forms: nonbullous and bullous. The nonbullous form is more common, accounting for 70% of all cases, and appears on the skin as a pustule or golden crusty sore surrounded by red infection. This form is usually due to Streptococcus pyogenes (strep) bacterium, but can sometimes be caused by the Staphyloccocus aureus (staph) bacterium.

If you are an athlete, you have a greater risk than most people of contracting impetigo, a highly contagious skin infection that affects about 2% of the global population annually. The term impetigo comes from the Latin verb impetere, meaning to attack. It refers to the breakouts or skin eruptions that characterize the disease. Impetigo has 2 forms: nonbullous and bullous. The nonbullous form is more common, accounting for 70% of all cases, and appears on the skin as a pustule or golden crusty sore surrounded by red infection. This form is usually due to Streptococcus pyogenes (strep) bacterium, but can sometimes be caused by the Staphyloccocus aureus (staph) bacterium.

By contrast, the bullous form of impetigo manifests as a macule or red rash that resembles a burn mark. It is due to staph bacteria which release epidermolytic toxins or poisonous substances that cause the lesions to form blisters (bulla is Latin for “blister”) or fluid-filled sacs called vesicles. Such vesicles tend to be thin roofed and easily ruptured, revealing a moist red infected layer beneath. After a few days, a golden crust will form over the blisters. Impetigo lesions can erupt anywhere on your body, but the most common sites are the nose and mouth, followed by the arms or legs.

While the lesions of either type of impetigo can be itchy, they are not usually painful. The bacteria are transmitted through skin to skin contact or through direct contact with contaminated objects. It usually takes 1 to 3 days after contact with strep, and 4 to 10 days after contact with staph, for the symptoms of impetigo to appear.

Who is at risk?

You are more likely to contract impetigo if you live in hot, humid climates. Additionally, poor hygiene and poor nutrition, as well as having diabetes or a compromised immune system, can make you susceptible to the infection. The condition occurs most frequently in pre-school and school-age children; in fact, 90% of all impetigo cases occur in children under the age of 2. Impetigo is the most common bacterial skin infection in children and is therefore sometimes referred to as “school sores.” Impetigo also occurs more frequently in athletes who play sports involving a high degree of physical contact than in the general population.

For example, if you are a wrestler, boxer, swimmer, gymnast, or football player, your risk of contracting impetigo is high, due to direct skin contact with other players, gym mats, and the showers in the locker rooms. You can also transmit or contract the disease if you share personal items with people such as clothing, towels, and bedding.

If you or a fellow athlete has a skin irritation from eczema, poison ivy, insect bites, cuts, or scrapes, it could easily become infected and develop into impetigo. For instance, one day you might notice that you have insect bites on your lower legs. You continue playing sports and doing your normal activities while waiting for these to clear up, but a couple of days later you find that the bites have now developed into crusty pustules. To avoid spreading the infection to your fellow athletes, you should abstain from playing and see your doctor.

How do you diagnose impetigo?

Your doctor can usually diagnose impetigo by taking a personal history and examining the appearance of your skin. However, as the skin patches associated with impetigo can resemble those seen in a host of other skin diseases such as eczema, psoriasis, poison ivy, lupus, or shingles, there is a chance that the condition could be misdiagnosed. To determine the particular type of bacteria causing your infection, and prescribe the best antibiotic, your doctor may take a culture using a swab.

How can you treat impetigo?

While impetigo may clear up on its own within 2 to 3 weeks, primary treatment consists of topical antibiotic ointments; more severe cases will also require oral antibiotics. Since impetigo is highly contagious, you should avoid close contact with anyone until 24 hours after starting the medication. After this, you may return to your normal activities, but be aware that your impetigo sores will take at least a week to heal completely. As an athlete, you should not be able to participate in sporting events until you have gone through a 72-hour course of antibiotic treatment, have no moist or crusty wounds, and have had no new lesions for at least 48 hours. You should not cover lesions as a way to allow you to participate.

What are the possible complications?

Left untreated, impetigo can develop into a more serious form of the disease called ecthyma. This condition occurs when the disease invades the second layer of skin, causing painful fluid or pus-filled sores that turn into deep ulcers and may leave scars. If you develop ecthyma, you may also have swollen lymph nodes. Other complications of impetigo can include cellulitis, another serious infection that affects the underlying skin. Even more rarely, you could suffer kidney damage from the bacteria that cause impetigo.

How can you prevent impetigo?

To prevent impetigo, avoid contact with infected individuals. If you touch an open wound, wash your hands immediately with soap and warm water. Wash any surfaces, objects, clothing, towels, or bedding that may have come in contact with the infection with soap and hot water. If you have an open wound or a fresh abrasion, avoid scratching as this could allow the bacteria from the impetigo to enter and cause an infection; better yet, cover all open wounds and insect bites. If you do contract impetigo, avoid spreading the infection to other people and to other parts of your body; Not scratching and applying antibiotic ointment and proper dressings to affected areas are imperative.

Know the facts, then act

Impetigo is a highly contagious bacterial infection of the skin that can sometimes have serious complications. It is spread through direct skin contact, which means everyone is at risk; athletes, particularly wrestlers, are at higher risk for contracting the disease. If you even suspect that you have impetigo, avoid contact with others until you know for sure you are not infected or you have been on medication for at least 72 hours. Knowing the facts and taking measures to prevent contracting or spreading impetigo will benefit you and your fellow athletes.

Author: Heather Martin, MS, LAT, ATC and Ashley Wojnowski, LAT, ATC | Columbus, GA

Reprinted with permission from the Hughston Health Alert, Volume 28,Number 4, Fall 2016.

Last edited on October 18, 2021